The good, the bad, and the Australian

/Australia is not all snaggers on the barbie and jolly swagmen. It is a land of contradictions. This week's Little Dogeared Books looks at two picturebooks—This is Australia by M. Sasek and Australia to Z, by Armin Greder— and explores what they might say about us as a country.

I turned six on a plane. We were making the long journey back to Australia from England, where we had lived for a few years, and I remember it specifically because the cabin staff came over with a slice of cake and sang “Happy Birthday” to me. They also let me visit the cockpit to see the pilot, which was quite exciting.

I also have a vivid memory from that trip, of my brothers and I practising our Australian accents. “Gerr-day mayyt”, we’d say. “Chuck another sna-ga on the barrrbie”.

I’m sure this was amusing to our fellow passengers, especially as we had all acquired quite distinct English accents by that time. But I remember being genuinely concerned that our grandparents and relatives, some of whom would be at the airport to meet us, would not be able to understand us unless we mastered this strange way of speaking by the time we touched down.

Australia to me at that age was a mythical land of red dirt, kangaroos, cork hats and endless barrrbies. Although it was the place I was born, it was foreign.

Needless to say, we soon found out that our Australian relatives could understand us perfectly. They instantly endeared themselves to us by giving us Bertie Beetle showbags—another peculiarly Australian thing. There weren’t any snaggers in sight, but once we were stuffed with chocolate, we didn’t mind.

A PLACE OF CONTRADICTIONS

Nowadays, I feel a strange mix of pride, anger, and patriotism about my country. I still gratefully breathe in the air and the wide open space when returning from overseas. I still love looking out the windows on a car trip down south, watching the burnt hills and the towering gums and the vivid blueness whip by with all the flickering nostalgia of a home movie.

But I also feel incredibly angry about a lot of things I see and read—by many of the decisions made by our leaders in our names.

Australia, to me, is a place of contradictions.

It is freedom, mateship, jocularity, compassion. And it is bigotry, single-mindedness, violence, dogmatism.

It’s a wide, wild, diverse ecosystem like nowhere else on earth, and it’s a government intent on mining and logging and drilling anywhere they can.

It’s home to the oldest culture on earth—to their amazing knowledge and lore and values—and it’s home to a willful refusal to recognise the trauma of our colonial history.

It’s an Immigration Minister threatening to send newborn babies to offshore detention centres, and it’s a State Premier (six, in fact) offering a home and safety to these babies and their families.

It’s all of these things.

The inconsistencies and contradictions of our country can be seen in everything from our arts to our notoriously changeable politics.

Two views of Australia

So this week, given that we have recently celebrated the problematic holiday of Australia Day, I wanted to explore these inconsistencies by writing about two picturebooks that I own. Two views of Australia, if you like. One is an old but classic book, a sort of ‘outsider view’, called This is…Australia by M. Sasek. And the other, a very recent release by author/illustrator Armin Greder, looks at contemporary Australia with an honest and unflinching eye: it is Australia to Z.

THIS IS AUSTRALIA

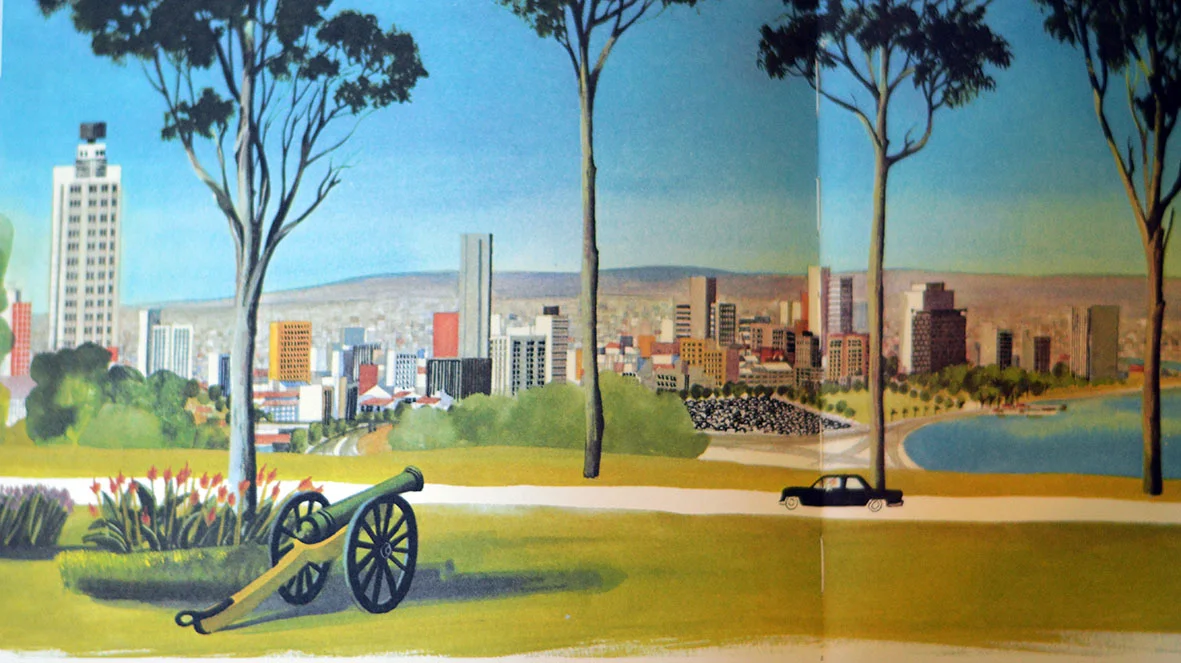

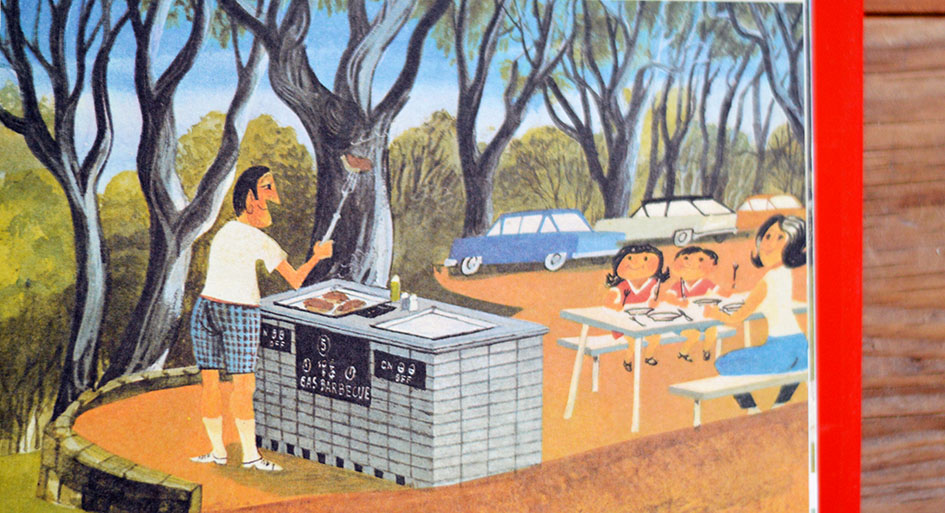

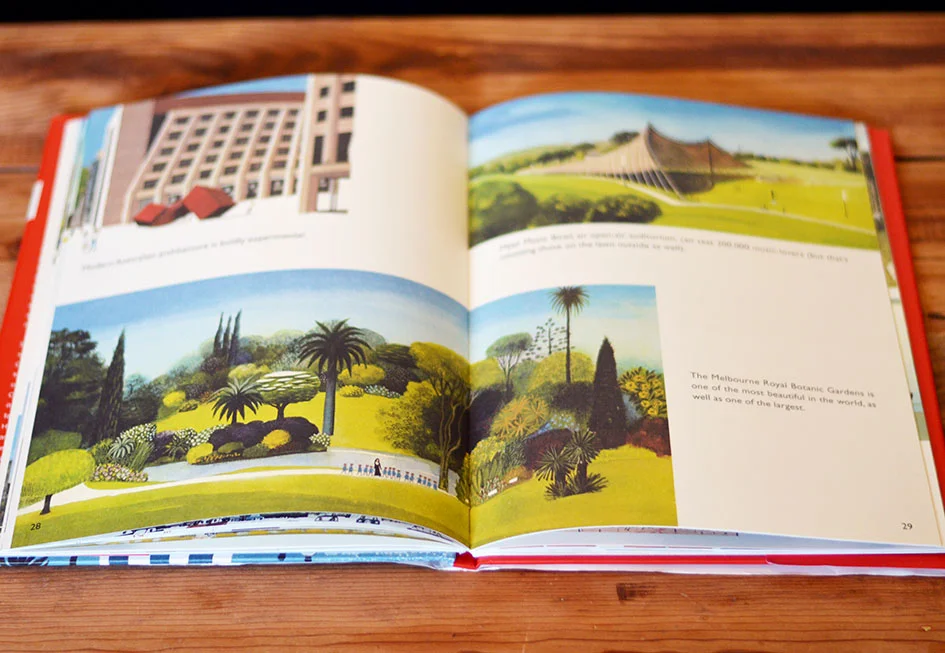

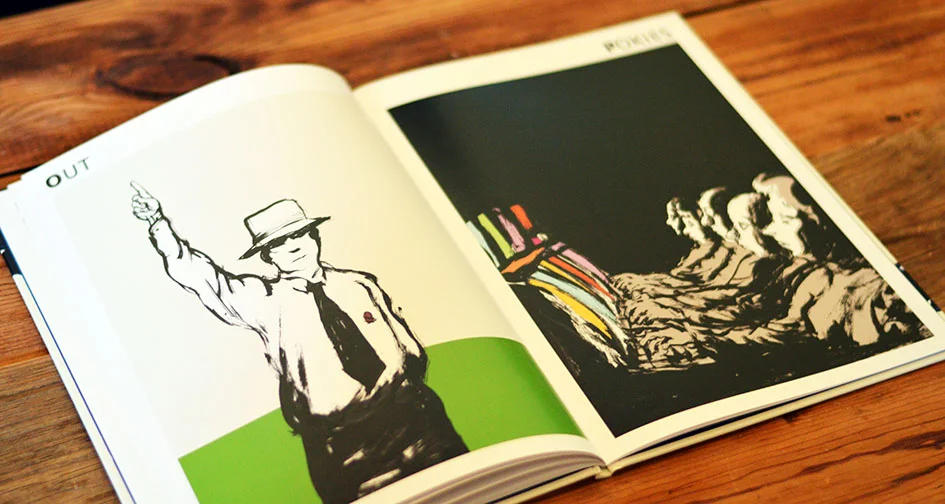

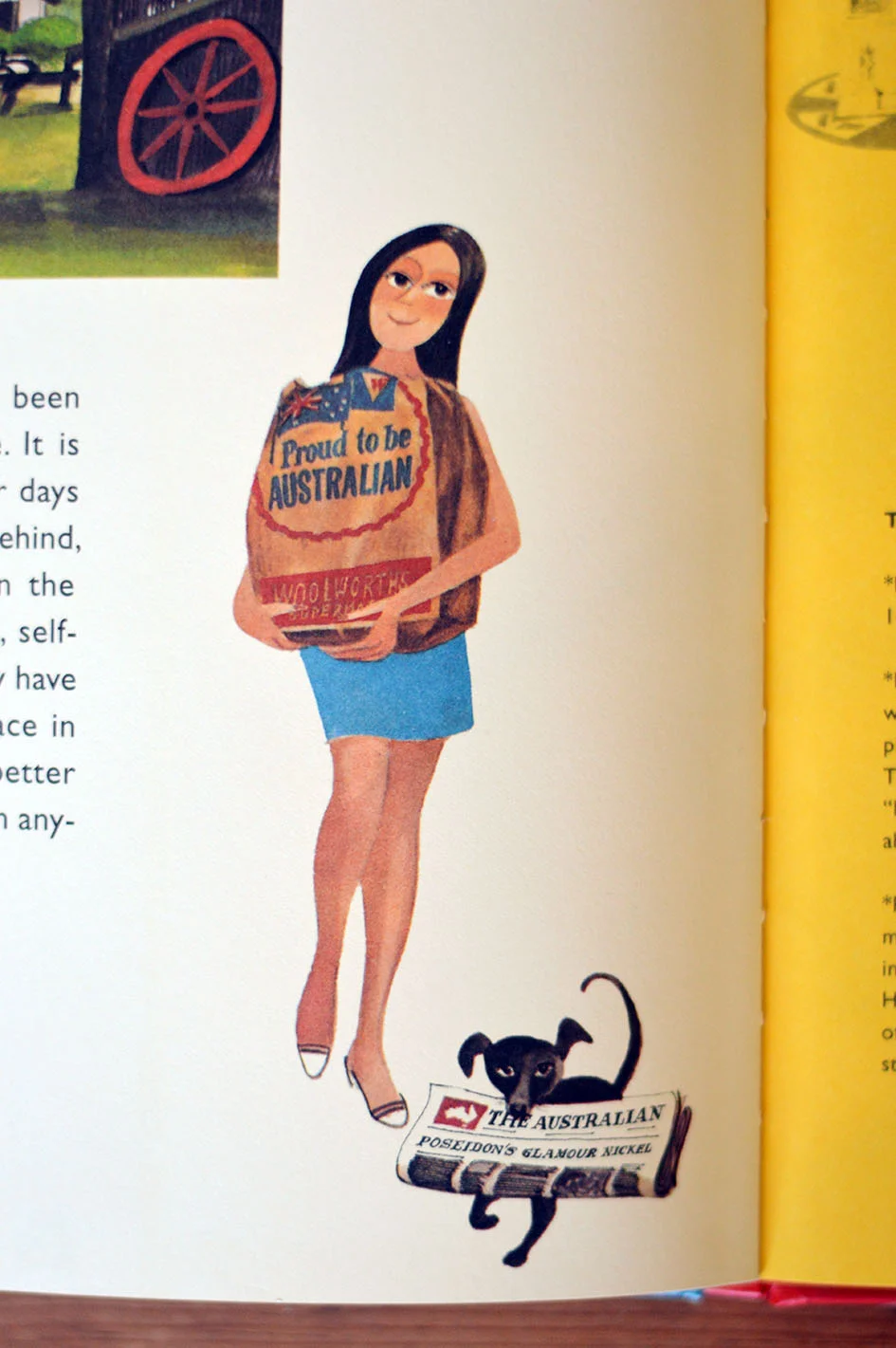

My dad used to collect M. (Miroslav) Sasek’s This is… books when I was growing up, and I bought This is Australia (Universe/Simon & Schuster, 2009 edition) myself a little while ago. Originally published in 1970, it takes us on a non-fiction journey through the geography and culture of Australia, accompanied by Sasek’s brilliantly retro illustrations.

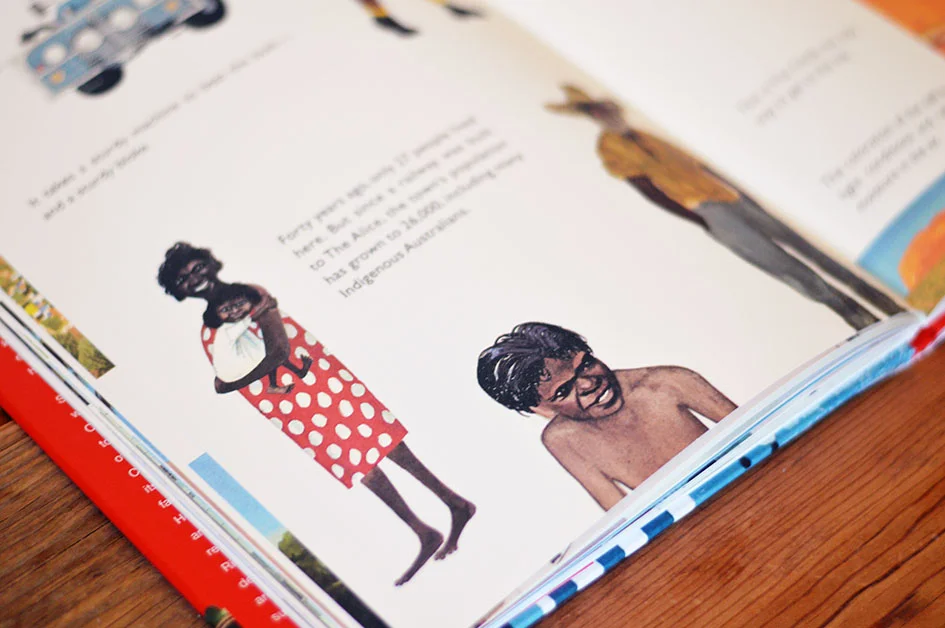

Some of the information is slightly outdated, as you might expect, although this edition contains a new ‘This is Australia Today’ section at the back. And while it does talk a little about Indigenous Australia, it focuses mostly on our colonial history and architecture, which is perhaps not surprising for 1970 (and while we have come a little further today, I still think we do not teach nearly enough Indigenous history, culture and language in our schools even now).

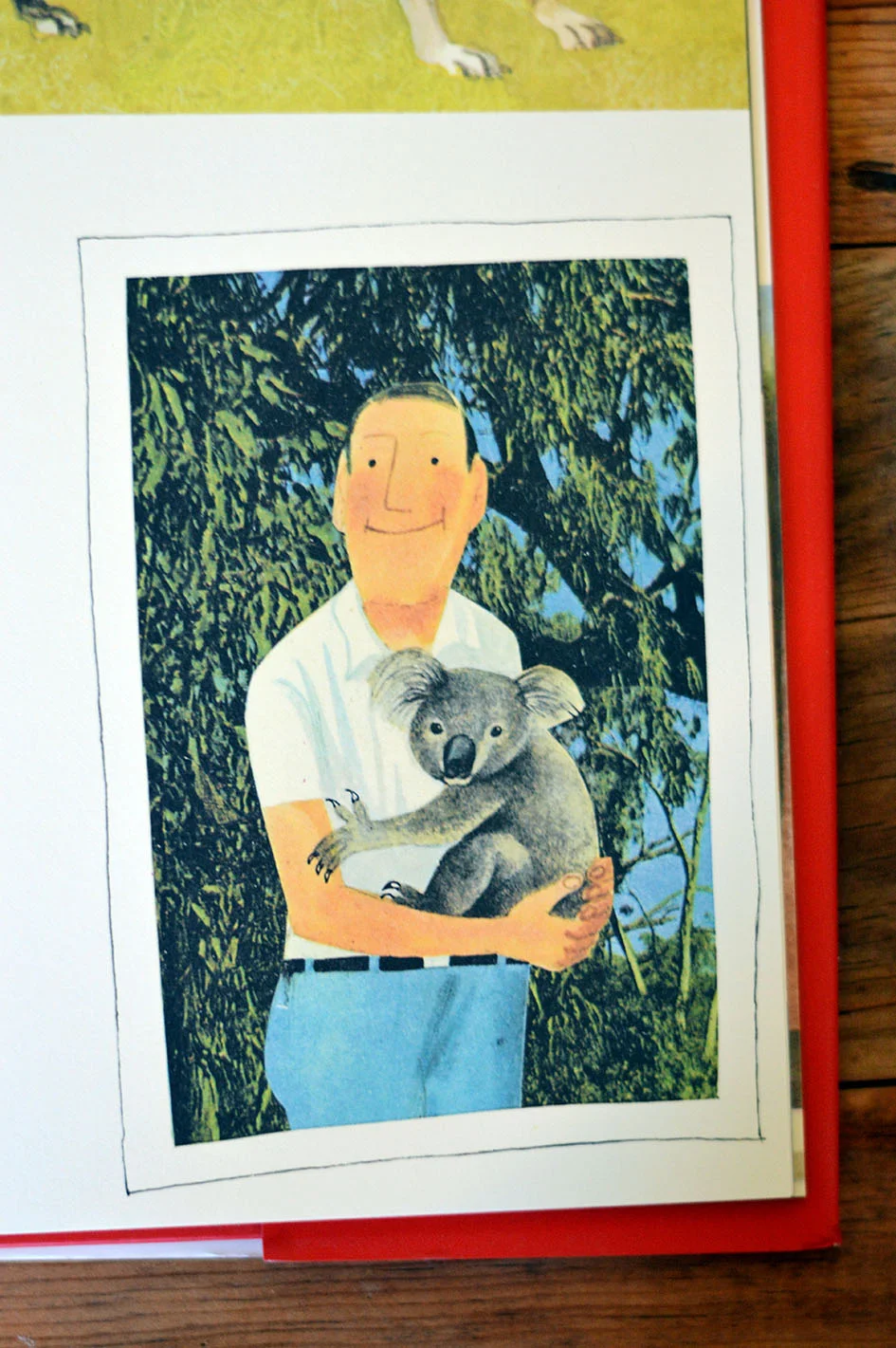

Set aside those problematic aspects, however, and you get quite a charming and fairly comprehensive look at our States and Territories, our wildlife, our land and our architecture. It’s not as visually impressive as some of Sasek’s earlier This is... books, but it nevertheless has touches of his signature magic; vibrant colours, stylised figures and detail.

It’s also lovely to see Perth and Darwin appear in there, when they are so often left out for a more East-coast focus.

The interesting thing about this book (aside from the Sasek charm) is that it reflects back to us, albeit in an old-fashioned way, the way the world sees us. The gentle koala (which the book tells us is the Aboriginal word for “not drinking water”), the happy kookaburra, the sails of the Opera House, the red centre—all of these are things that the world still associates with us as a country. It exists as a slightly quaint, mostly harmless, visually pleasing account of Australia through the eyes of an outsider.

This is contrasted completely by Armin Greder’s picturebook.

AUSTRALIA TO Z

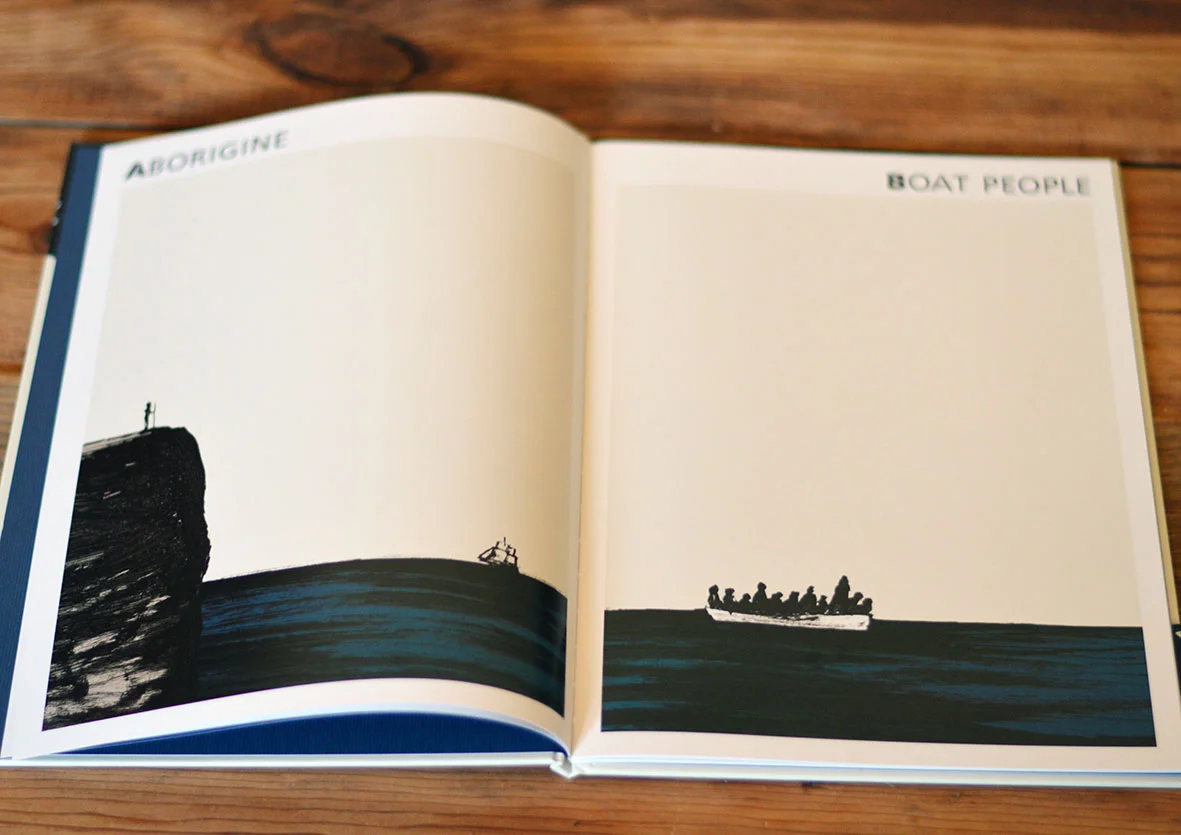

Australia to Z (Allen & Unwin, 2016) also makes us reflect on how the world might see us, and how we in turn see ourselves. But it provokes some very different, and much more unnerving, feelings.

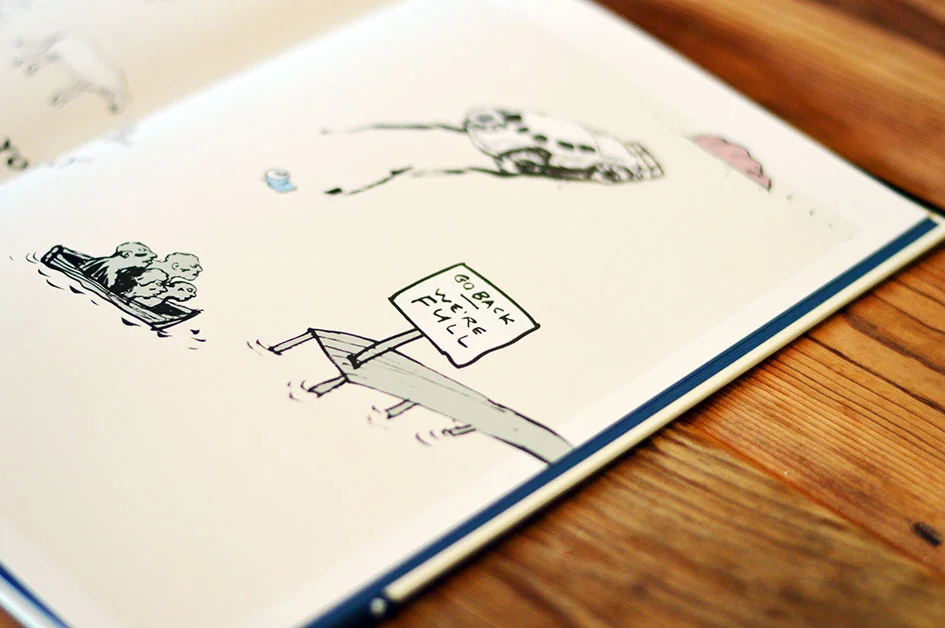

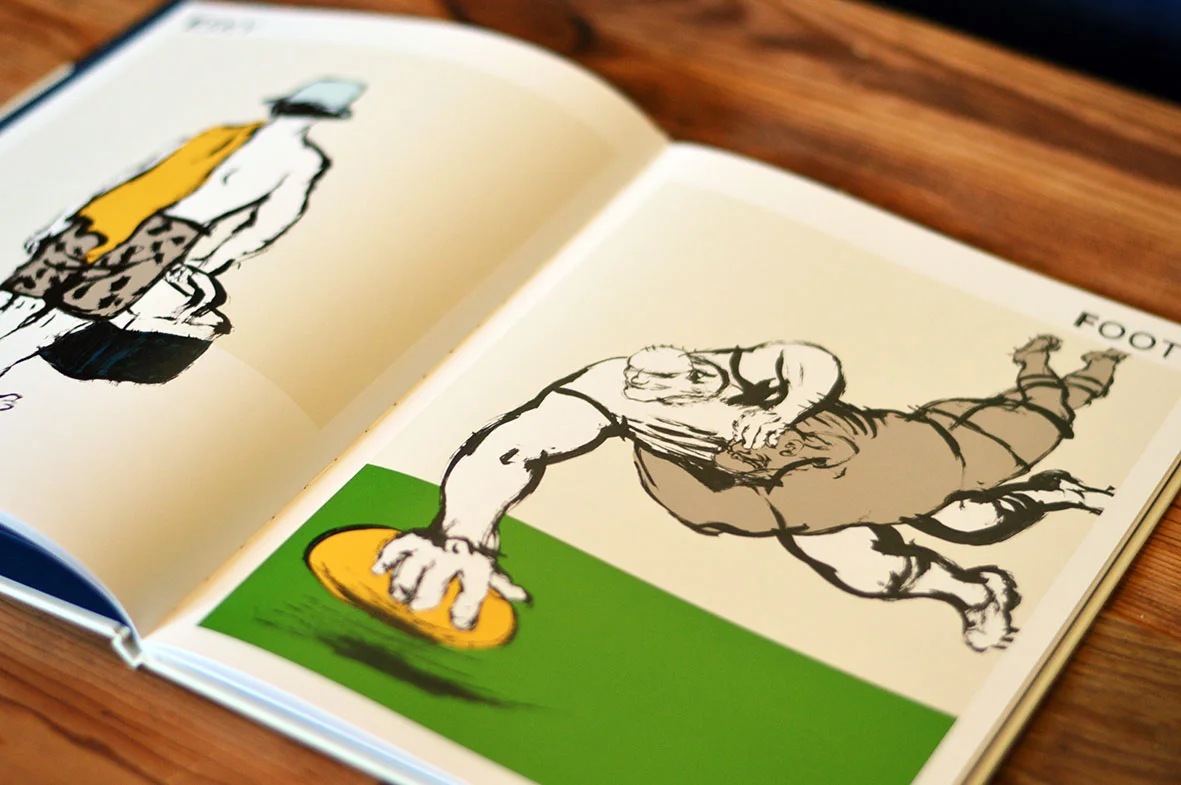

I bought Australia to Z just a few weeks ago, very soon after it was released, and immediately I knew I had to write about it. At first glance it looks like a typical children’s alphabet book (they’re called ‘abecedarians’, I discovered recently), with a patriotic twist. Inside, it is strikingly graphic, with Greder’s loose, expressionistic strokes bursting onto the pages in a black ink frenzy.

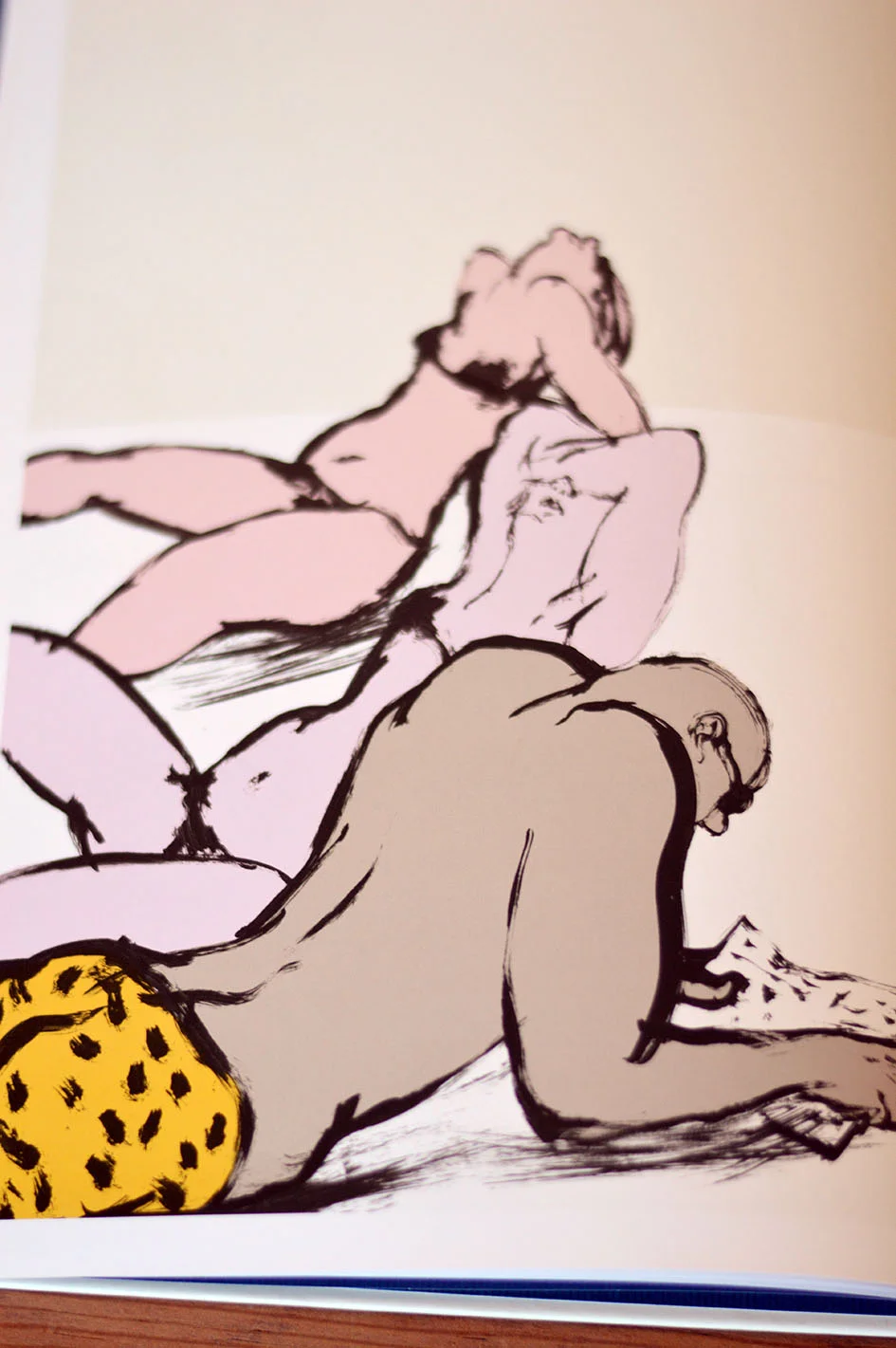

As you flick through it, however, you start to get the idea that maybe this is not all that it appears. Maybe this book is not aimed at children who are learning their alphabet. For there are some darker and much more disturbing currents running beneath the pictures of thongs and Vegemite and eskies.

It is very disconcerting to see hints of our societal anger and violence appear in what, for all intents and purposes, looks like a children’s book. But it is also a powerful comment on the darker side of our society and our patriotism.

The virulent rage and impatience Greder conveys—with just a pair of eyes seen in a rear-view mirror and a hand slamming a car horn as a kangaroo flashes past—is disturbingly real.

Greder’s books always deal with difficult and often political issues, and the courage with which his illustrations speak is admirable, particularly for a children’s author. The fact that this book was even published actually surprises me, because I know how risk-averse contemporary publishing is. It says something about the magnitude and standing of Greder’s work. He unflinchingly portrays the good alongside the bad—the darkness along with the light—in a way that our politicians and leaders wouldn’t dare to.

The violent gestures of two footballers in a tackle, or a group of bodies slouched slavishly on a beach, or the greedy relish with which a mouth bites into a meat pie, are so immensely discomforting precisely because I understand them so very well. I don’t want to understand them— in fact I wish I could dismiss them. But I can’t.

I can so clearly see the greed and the aggression and the intolerance of our society reflected here. Racism, homophobia, misogyny, corruption—to ignore that these things are part of our society is as blind as thinking that we all ride kangaroos to work.

For all the amazing things about the place we call home—our landscape, our people, our culture, our lifestyles—there are many things that aren’t so amazing.

And the pain and trauma go so deep with some of these issues, that Greder’s simple, sparse ink drawings seem to be the only appropriate representation. Somehow they are perversely suited to a picturebook, where words would be empty but ink lines carry the gravity that the subject requires.

Where to now?

Although Greder’s book may not be suited to all children, or even to all teenagers (who I think it is probably directed at), that isn’t to say that there aren’t some who would respond to it. As I wrote a little while ago, letting children explore and respond to dark things when they are ready to, rather than pretending dark things don’t exist, shows them that we respect their intelligence. And letting them have a say in their country, and its future, is more important now than ever.

Even if you don’t think your children are ready for a book like this, then maybe consider reading it for yourself. It is both a picturebook and a politically outspoken account of contemporary Australia, which asks us to think hard about who we are as a nation, and where we are going.

For some reason, the contrast between these two picturebooks perfectly encompasses the internal conflict I feel about my country and its contradictions. Australia is not just cute marsupials and heat and gum trees and endless barrrbies. It is much, much more than the stereotypes and the tourist brochures, and there is real value in acknowledging that.

Fiona.

Australia is not all snaggers on the barbie and jolly swagmen. It is a land of contradictions. This week's Little Dogeared Books looks at two picturebooks—This is Australia by M. Sasek and Australia to Z, by Armin Greder— and explores what they might say about us as a country.