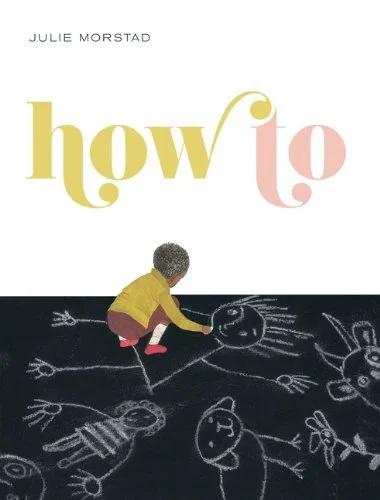

"How to" by Julie Morstad

/In our changing world, the Arts are valuable not because they come with all the answers, but because they encourage us to question everything. Like the Arts, How To shows us the value in being ourselves, thinking creatively, and learning how to wonder.

Just recently, a number of Western Australian writing groups and literary organisations lost their State funding. This came after disastrous federal cuts to the Australia Council in 2015, followed by a further $52.5 million gutted from the sector at the end of the year, including from galleries, museums and Screen Australia. Where did the money go? Well, warplanes and commercially-run immigration detention centres for a start. But the arts didn’t totally miss out. A big chunk of money was redirected to fund the filming of the Hollywood sequels to Thor and Alien.

Yes, you heard that right.

The complete decimation of the Arts in Australia is both horrifying and numbingly depressing. It takes me back to the end of high school, when my decision to study Arts was met with looks of confusion and incredulity. ‘But you could do Law! Or medicine!’

Most Arts grads have encountered these attitudes. Going on to do a PhD in poetry, of all things, only amplified the issue. I still find myself apologising for my choice; acknowledging the oddness of it, laughing self-deprecatingly before anyone else can. ‘A poet? What use is that? Ha ha ha.’

In fact, I believe that poetry is essential to humanity.

One line can hit you like an electrical charge, spreading instantly across the surface of a deep pool of memory, thought and sensation.

It opens up new worlds and new connections, and gives something that may have been quite mundane —a red wheelbarrow, or a field of daffodils, or an ‘evening spread out across the sky’—a whole new, magical, existence.

Poetry, more than anything else, showed me how to wonder. And that is something that I can use every day of my life, in every single thing I do.

‘I’D LIKE TO STUDY ARTS, BUT I WANT A GOOD JOB’

Devaluing the arts is a dangerous thing. I see it in the rhetoric of tertiary education, where science and engineering are elevated as ‘careers of the future’ and the Arts are reduced to pretty words and pretty pictures. It happens in politics, where Arts orgs are seen as a cash-burden better used for funding other things (like warplanes). I see it in young grads who say things like ‘I’d love to study Arts, but I want to be able to get a good job so I chose Commerce’. In a world that requires more accountants and marketers than poets and painters, I still think something is not quite right.

The fact is, this attitude appears wherever money makes decisions.

But surely the things that the Arts give us—creativity, empathy, the ability to question and analyse, to learn from the past, to look critically at the world, to think laterally and create connections, to innovate—are worth far more? Aren’t they the most important things we could ever encourage in a generation that will have to deal with catastrophic climate change, global unrest and a ballooning population? Devaluing the Arts is not just a pity; it’s an immediate danger to our future.

WHY IS WATER WET?

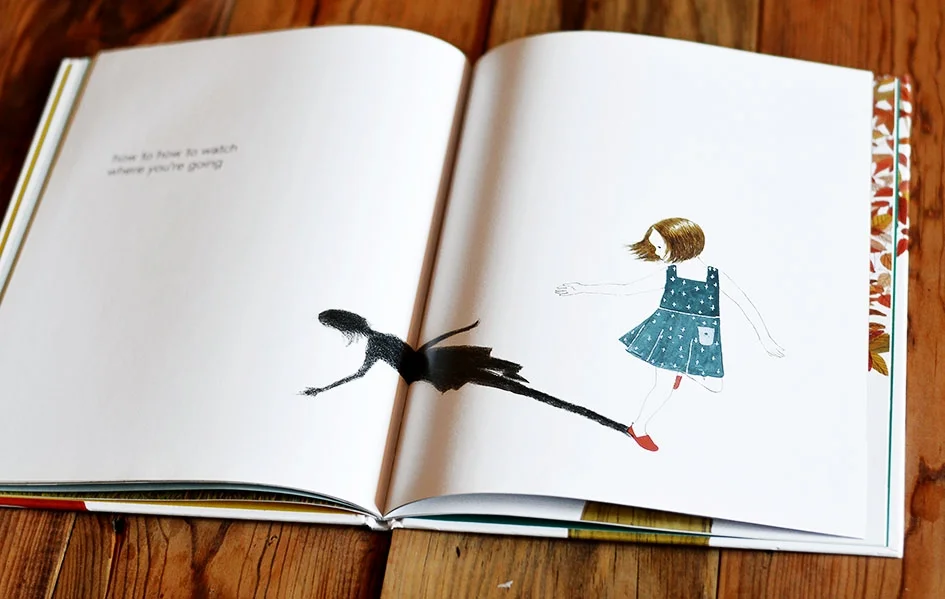

As children, the ability to question things comes naturally. A pre-primary child, with supreme unselfconsciousness, might ask:

What is a shadow? Where did the sky come from? Why is water wet?

They don’t care about looking ignorant, or whether they might be asking ‘stupid’ questions. They’re simply curious. They want to know. I’ve heard that three-year-olds can ask upwards of three hundred questions a day, and as much as that drives their parents crazy, it is invaluable for learning. So too, the Arts encourage us to question everything—to test our assumptions, to prod our biases, to see things through other lenses.

But in a world where the Arts are consistently devalued and funding is withdrawn—where depth and meaning and analysis are glossed over in favour of hard data—we are increasingly forgetting how to ask questions. We yearn to be told what to think and do—to have someone else take responsibility for our decisions. We look to science and technology, to the economy and our governing bodies, and to politicians and the media to tell us how to live.

We google things like ‘how to find love’, ‘how to leave your job’ and ‘how to be happy’, in the hope that the Internet can give us answers.

We are too often discouraged from probing and making meaning out of the information we’re fed. Questioning is frowned upon, particularly if it leads to resistance (I know this not least because I recently attended a workshop, in my own organisation, which explicitly preached the value of compliance and the dangers of resistance). The devaluing of the Arts is both a cause and a symptom of this mindset.

HOW TO… BE A MERMAID

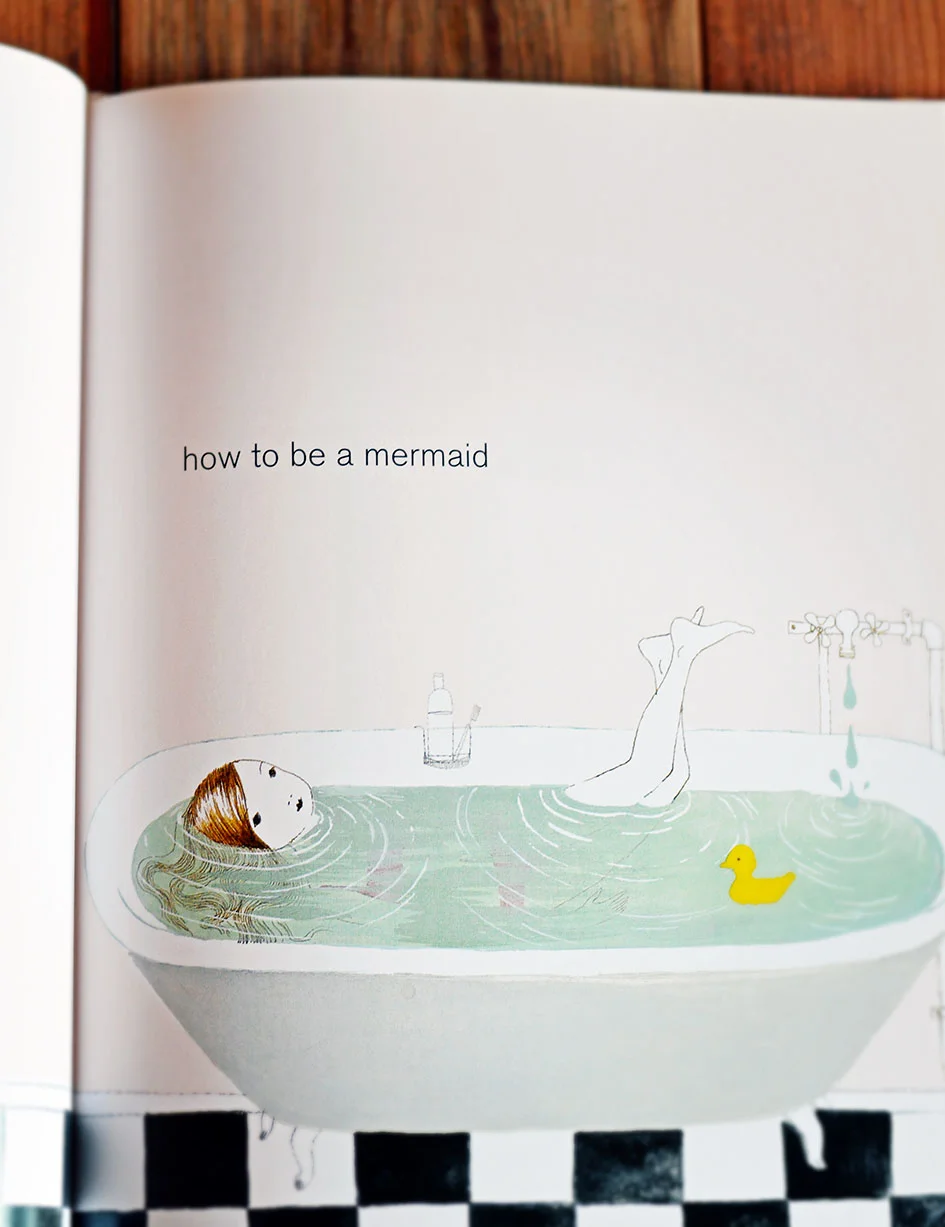

In light of all these turbulent thoughts I’ve been having, the book I chose to write about this week is Julie Morstad’s picturebook How To (Simply Read Books, 2013). I love this book because it seems to deal playfully with this modern dilemma of ‘being told’ versus ‘finding out for yourself’. It pretends to give us all answers, but they turn out not to be the ones we were expecting.

This book mirrors our adult obsession with being told what to do. But it takes our often-googled plea for answers (’how to be happy’), and subverts them the way a child would.

How to be a mermaid? Like this.

How to disappear? It’s easy.

The text and the illustrations play with each other like a toddler with a parent— enquiring, cheeky, full of childish delight. Morstad’s lyrical drawings are offset by blocks of solid colour and sparse text. The penciled lines of her children dance and run and climb happily over the pages, wide-eyed and tousle-haired.

How To has a vintage feel to it, but the graphic simplicity of the book’s design is refreshing and modern—I’ve always thought Julie Morstad is a genius in the way she uses white space. It makes her drawings and their colours absolutely sing. That, together with the scant text, makes reading this book a little like delving directly into the mind of a child.

And even though this book has no distinct characters, plot, or even setting, Morstad’s illustrations give it so much warmth and heart it feels as though each of these children could be someone you once knew— a long-lost best friend from kindy, a neighbour’s child, a group of children you walked past once while on holiday in Europe, flying kites in a park in a drizzle of rain.

THE WAY A CHILD WOULD

The brilliant thing about this book, then, is that is also seems to make fun of our adult obsession with instructions. Telling a child How to be a Child would seem ludicrous to them, yet I’m certain I’ve seen online articles and books proclaiming to tell us how to be adults, how to live our lives. How To shows us the ridiculousness of that. It suggests that we could instead approach things more like a child would: creatively, imaginatively, discovering new worlds in even the most mundane things. Doing things our own way.

And therein lies the value of the Arts. Like Morstad’s book, the Arts show us that disappearing, or being a mermaid, or finding innovative solutions to the world’s problems is easy—if only we think beyond the Google search box.

The Arts, like this book, can show us how to be brave and how to be happy, not because they come with all the answers, but because they encourage us to find out for ourselves.

Even more importantly, because they show us how to wonder, just the way a child would.

Which is a very, very valuable thing.

Fiona

Australia is not all snaggers on the barbie and jolly swagmen. It is a land of contradictions. This week's Little Dogeared Books looks at two picturebooks—This is Australia by M. Sasek and Australia to Z, by Armin Greder— and explores what they might say about us as a country.