And what of the Nightshift Shelver?

/Words and images BY Michelle Astrid Francis

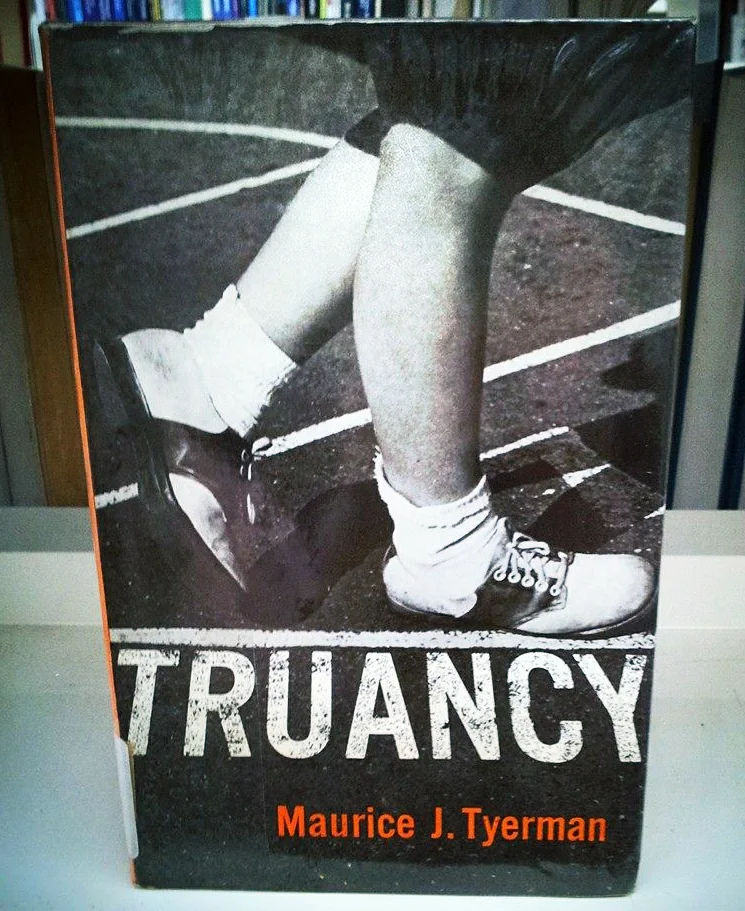

Cover Illustration by Ant Gray

There are few noble professions left unspoiled by controversy. Take the all too common occurrence of pyromaniac firefighters, corrupt cops and sinful priests. But with librarians, it’s different. As Michelle Astrid Francis shows us—in her first essay for Rabbit Hole—your average librarian is not only guardian of the stacks, but also a gatekeeper to imaginary worlds beyond.

I love the opening library scene in Ghostbusters—hands down, best library scene in a movie. Clue, Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade, the whole mis en scène of The Breakfast Club don’t rate too badly either. Then there’s all of Party Girl because, you know, PARKER POSEY. And how about the scene in Suddenly Last Summer where Elizabeth Taylor is taken to the library by a hard-ass Nun before being released into Montgomery Clift’s dubious care; or the cold, dark, Thatcher Memorial Library in Citizen Kane?

If we segue to television, Seinfeld’s library episode is a pop-culture classic along with pretty much any episode of Buffy (but be honest, is the appeal the library or is it Giles?), and Doctor Who’s David Tennant era ‘Silence in the Library’ and ‘Forest of the Dead’ are a mythical, metaphysical, library-space-dream.

As well as being a ‘Spotto!’ exercise for library tragics, the library is an oft-used trope in film for a character searching for reason and meaning. It stands as a portal to understanding others, and ostensibly, ourselves.

Scouring the shelves, reaching out for more books, reading feverishly, a character comes to terms with humanity’s cruelty and suffering, assembling the unknown into something recognised. Knowledge is acquired, adversity is faced, and misfortunes overcome.

But what about a movie where the books are reaching out to us? Seeking our attention? Maybe not floating off the shelves in a Ghostbusters sense, but what if all those unused automotive manuals, social etiquette guides, sociological discourses on delinquents and vagrants, outdated technological tomes, niche guides on wicker furniture making and Nordic knits, were lying in wait? Books once deemed worthy of selection but now suspended in time—relics of human-kind’s thoughts, obsessions, and beliefs circling vacantly—biding time until someone... uh... picks them up. And then... uh.... takes a photo. And then... uh... shares them on social media.

Okay, you’re right; I probably wouldn’t go and see that movie either. Unless the books committed atrocities or forced others to (and I don’t know about you but I found the namesake of The Babadook a pretty embarrassing horror entity sitting awkwardly at the heart of an otherwise solid psychological horror film, so I’m not going to get my hopes up for a slew of new ‘possessed-by-books’ genre films).

But in some way, this is a long means of going about saying that such books have been seeking my attention for a couple of years now. I don’t know when they are going to appear or make themselves known. Sometimes I try seeking them out but they can be cagey and don’t materialise. But the ones that do appear—the ones that exist in a societal vacuum, sealed under a bell jar—I call my ‘Library Finds.’

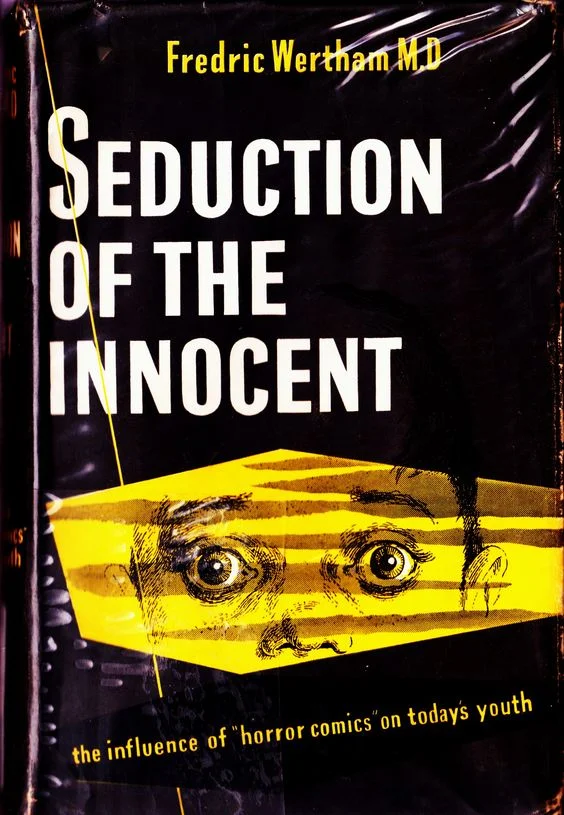

These books are a glimpse of memory that isn’t my own, exploring cultural preoccupations from a mere decade past, or maybe a century ago. Textures. Fonts, glorious fonts. Absurd titles. Camp and earnest blurbs. Hand-printed etchings. Arresting covers.

Once a book has made itself known to me, I then share that find. Selected just one more time, these books end up being viewed by many; metaphorically riffling their pages, sparking curiosity or merely a moment’s amusement, the gift of social media provides these books a new audience. A friend once asked me, “Where do you find all these treasures?” And as clichéd as it sounds, I replied, “They find me.”

It’s true. They find me.

Discovering gems in Dewey Decimal disarray

I spent two years working as a Nightshift Shelver, while studying to be a librarian after deciding I was thoroughly over the arts sector. After years of working in under-funded, over-worked environments, often dealing with fragile temperaments, and finally working out that as a generally introverted personality type working in theatre (it’s not quite the contradiction you may think), the networking, self-promotion, and advocacy required to do my job well, had worn me thin.

I’m still not 100% sure why I went for libraries. To be a librarian certainly has nothing to do with liking books, although I can guarantee it is why so many of us got sucked in. The paradox I experienced as a library student was that I never went near a physical library. I was an external student and academic journal databases were the life and breath of my learning; all of which I had gloriously free access to because my university library subscribed to them for me.

And so, as a student, the only time I spent with books was on my nightshifts.

After a draining day studying, I thought all I wanted in life was to have my own trolley and access to the collection. But I could only spend moments, stolen time, with the books.

The pressure to empty my trolley was very real. Statistics were kept on how many books were shelved each night. Lord, but libraries love statistics. I had more trolleys than I could handle! My supervisor always wanted more! And faced with the Dewey disarray left behind by students night after night, I knew no one was asking themselves, ‘But what of the nightshift shelver?’ as another title was flung to the floor distractedly. I should have been careful what I wished for.

The wonderful thing about shelving is that you don’t know where you’re going to end up; what strange digest is lying quietly in wake to catch your roving eye. I may have shelved a book with no particular interest to me, but then just a little way across and down the shelves, something would grab my attention: a hand-printed titled etched on the spine, a magnificent font, uneven binding, a striking cover, an obtuse title, the strange selling-point of the blurb. Any or all of these things have made me pick up a book and want to put it in someone else’s hand: Look! At! This!

Instead, alone, and aware I could only spend a few short minutes enjoying its presence, I would take a snap of my ‘library find’ and post it to social media. At some point, I noticed the Library Finds were often the first topic of discussion I had with acquaintances; they were a good ice-breaker in social situations or a moment of connection with people I didn’t know very well.

This was tapping into something for so many other people. What was it?

Haunted realities and the Art of donkey keeping

Hauntology: “Replacing the priority of being and presence with the figure of the ghost

as that which is neither present, nor absent, neither dead nor alive.”

(Hauntology, spectres and phantoms—Davis, C. 2005)

After Rabbit asked me to write this guest post, I’ve had to think a lot more about the presence of the Library Finds. Why was something that was relatively organic and haphazard for me, garnering interest with others?

While it feels perhaps 10 years too late to be writing anything fresh about it, I guess I would say the Library Finds is another manifestation of ‘hauntology’ acting upon and within us. The term hauntology, a play on ontology (which in French sound exactly the same)—was first conceptualised by Derrida in Spectres of Marx: The State of the Debt, the Work of Mourning & the New International (1993); a collection of lectures he delivered on the future of Marxism, following the declaration that communism was ‘dead’ by commentators such as Francis Fukuyama, upon the 1989 fall of the Soviet Union.

Derrida dissected the substantial ghostly symbolism in Karl Marx’s writing, and considered how such ideological spectres incessantly haunt a historicised present. In his 2009 blog piece, Adam Harper explains that in this respect:

“History haunts (Marxist) ideology, and (Marxist) ideology haunts history; Utopia haunts reality and reality haunts Utopia, theory haunts practice and practice haunts theory, and so on.”

In respect of artistic theory and practice, hauntology was immediately appropriated and interpreted through the fields of visual art, fiction, and electronic music (epitomised by labels Ghost Box and Mordant Music) and peaked throughout the naughties, producing work within a paradigm that Harper summarises as “visited by nostalgia for an ongoing utopian promise, yet haunted by a reality that was never going to make good on it.”

And here the Library Finds live, haunting us with ensnared idylls and eradicated ideals. To paraphrase Derrida, without doing anything, they possess an identity which neither belongs to us or to them: they are merely haunted by what they were and by what they are now.

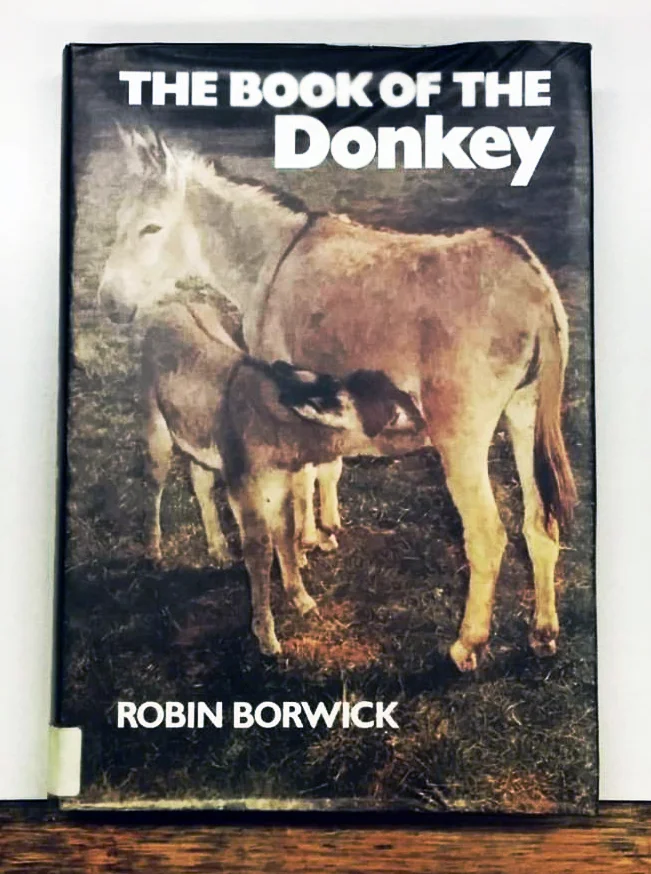

An idea, I like to think that encompasses the art of donkey-keeping.

You think no one ever had utopian preoccupations with donkey-keeping? You’d be wrong. Robin Borwick loved donkeys so much, he wrote at least three books on them:

“The first book to be published dealing only with the donkey was ‘People with Long Ears’ by Robin Borwick in 1965. Later, in 1970 Borwick wrote a paperback called simply, ‘Donkeys’. In ‘The Book of the Donkey’, the author discusses the donkey as a pet and the best methods of making it thoroughly responsive.”

Was there ever an ideological movement for bridging a relationship between man and his donkey? Or was it merely an unrealised futurist dream of beastly harmony? This little figure of the ghost teems with utopian promise but remains an object “haunted by the increasingly dystopian qualities of reality” (Harper, 2009).

In other words: Donkeytopia haunts reality; reality haunts donkeytopia.

Following the trolley’s pull

Okay, I’ve probably stretched the ‘hauntological’ aspect a bit too far with the donkey example, but that’s the other thing that I think the Library Finds tap into for people: they are a promise, a launching ground for imagining. What exists between the covers? I promise it will never be more interesting than what you are dreaming up right now.

Displacements is one of my favourite Library Finds that does this—the fear or compassion induced when I see that hard bright silver embossing against the stark puritan cloth.

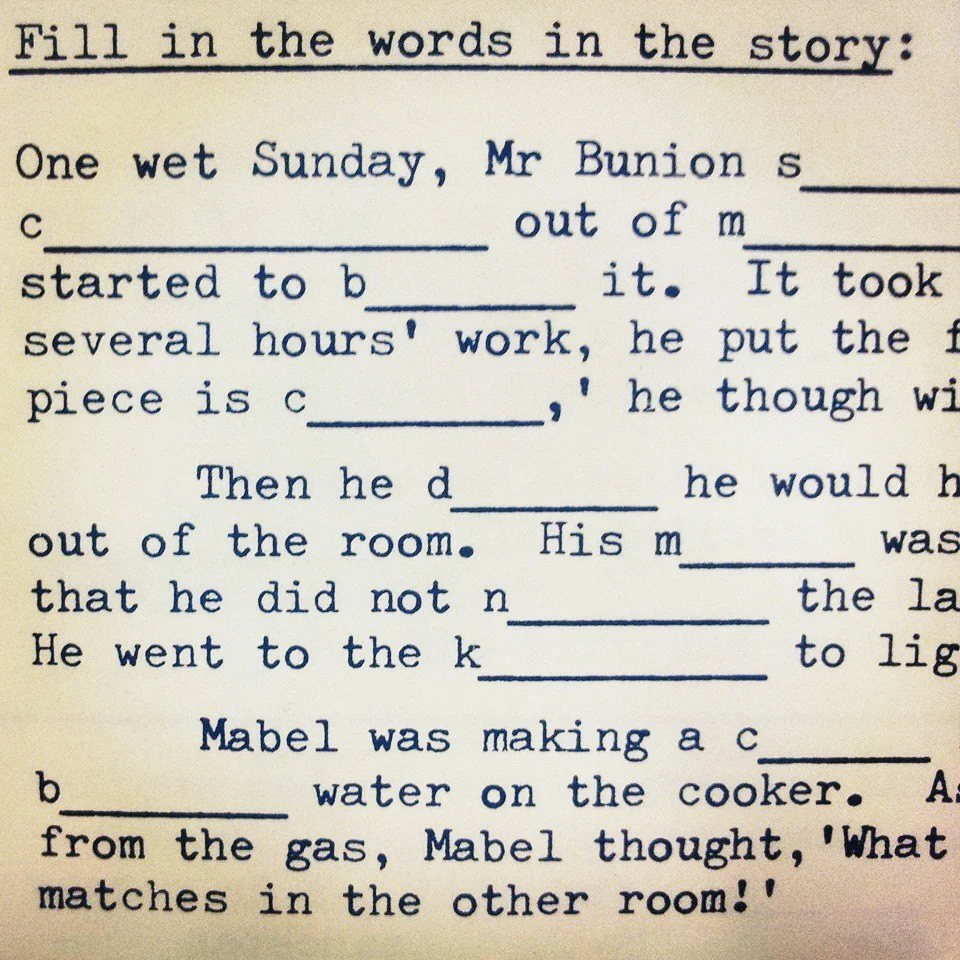

Displacements. A story is beginning within: Loss, suffering, endurance. Belonging. The idea floats for a moment then breaks off; slender, a tremor, now gone. The stories bubble up, some dissolve, and others stay. For instance, I was at a bar one night, seeing a few local bands. One of my friends was part of the line-up, and I had a brief chat with him before he was on. Shouting to make himself heard over the music, he told me about one of the Library Finds that had stuck most in his mind. It was one of my earlier finds, a page from a school primer where the students had to fill in the words in the story. My friend confessed upon seeing this image that he filled in every missing word with the foulest and most offensive words he could possibly draw up from the dark depths of his soul.

It was funny, sure, if not a little alarming—but what I loved most was that the image had tapped into my friend’s imagination and turned a grammar exercise into some kind of exorcism. Whatever was tormenting him had found a safe place for expression within those blank spaces between the words.

This friend is a drummer with amazing kineticism, a mixture of restraint and fluidity all at once. After our chat, watching him play, I wondered, was he so calm and easy on the skins because he regularly vented his frustration and restlessness through the little writing exercise? It’s probably not; in fact I’m sure it’s because he’s a serious talent. But that’s what the Library Finds do. They worm their way in and new stories and speculations abound.

I am no longer a Nightshift Shelver, but my commitment to the Library Finds remains the same. I just have to carve a little more time out of the week to plant myself within the shelves and wait for their call.

What I didn’t realise at the time this all started was this: with one’s own trolley comes great responsibility.

The humble library trolley was the portal into this whimsical obsession, and perhaps remains at the heart of it, for the shelver must go as the trolley dictates; the Library Finds the reward for Dewey diligence.

Michelle currently works as a Public Library Liaison at the State Library of Western Australia. She has worked as a freelance arts writer and reviewer for artsHub and RealTime Arts magazine. Her dream is to act out the opening scene of Ghostbusters as a synchronised flash mob experience on a global level. She recently got her first tattoo rather than purchase a new washing machine. She is comfortable with her priorities.

Want more Library Finds? Follow Michelle on Instagram (@libris_invenit) and check out her Library Finds board on Pinterest.

Painter Tracey Read talks about spending four weeks painting and drawing her way around Italy.