The Teacher as Class Clown

/Words and Illustration by Ant Gray

Author H.G. Wells had some great advice for writers, which is equally good advice for teachers too.

It’s almost the end of semester and I feel beaten. Every week I think, ‘This is the week it’s all going to fall apart,’ but miraculously, it hasn’t so far.

Three months’ worth of lectures and workshops delivered, all to a bunch of students who are starting to look as worn as I am. And then there’s the teetering pile of essays full of poorly formed sentences waiting to be corrected, leaving little time to write any poorly formed sentences of my own.

And so every week is a mountain, and every week I think I’ll slip scaling it, bringing everything—students, admin, the piles of marking—all cascading down around me.

But by Friday morning, the worst is over. Ninety percent of the work is done, so I can breathe easier having survived another week. This week, for some reason, I woke up thinking about H.G. Wells—you know, the author of War of the Worlds, The Invisible Man and The Time Machine. I was thinking about one of his essays I’d read on the subject of, well, “The Art of Writing Essays”.

“The art of the essayist is so simple,” Wells says at the start, setting up what I think is a long hard pull of the reader’s leg.

“One must needs wonder why all men are not essayists. Perhaps people do not know how easy it is. Or perhaps beginners are misled. Rightly taught it may be learnt in a brief ten minutes or so, what art there is in it. And all the rest is as easy as wandering among woodlands on a bright morning in the spring.”

So what stops an aspiring essayist who has the urge, but doesn’t have the talent to see it through? What is the novice lacking that the master never begins without?

A pen. That’s all—a pen.

Every essay begins with making sure you have a pen.

“Mark this, your pen is a matter of vital moment. For every pen writes its own sort of essay, and pencils also after their kind. The ink perhaps may have its influence too, and the paper; but paramount is the pen. This, indeed, is the fundamental secret of essay-writing. Wed any man to his proper pen, and the delights of composition and the birth of an essay are assured. Only many of us wander through the earth and never meet with her—futile and lonely men.”

And so from here Wells plays with us some more, like a hulking Great Dane with a squeaky toy, telling us about different types of pens and their virtues. Quills, for instance, are best suited to literary prose, suggesting a ‘faintly immoral’ quality. “The quill is rich in suggestion and quotation,” he writes, even “in the hands of a trades-union delegate.” And if you prefer a pencil, he advises, you can still write well, but the effect is “blunter than quill work and more terse.”

Typewriters? Forget it. As Wells writes:

“No essay was ever written with a typewriter yet, nor ever will be.”

And then there’s a lengthy-ish exposition on writing paper…

“The luxurious, expensive, small-sized cream-laid note is best, since it makes your essay choice and compact; and, failing that, ripped envelopes and the backs of bills.”

And what type of ink to use…

“The ink should be glossy black as it leaves your pen, for polished English. Violet inks lead to sham sentiment, and blue-black to vulgarity. Red ink essays are often good, but usually unfit for publication.”

So by now, I’m sure, you can see how much he delights in screwing with the reader because two paragraphs from the end, he drops the buffoonery and gets right to the point.

“This is as much almost as anyone need know to begin essay writing. Given your proper pen and ink, or pencil and paper, you simply sit down and write the thing.”

That’s it. That’s his advice.

Over his lifetime, Wells wrote some 120 books, many more of them non-fiction than fiction. But two hundred words short of this eleven hundred-word essay, the sum total of his advice amounts to, ‘Want to write something? Simply sit down and write it.’

Mood before matter (pipe and slippers optional)

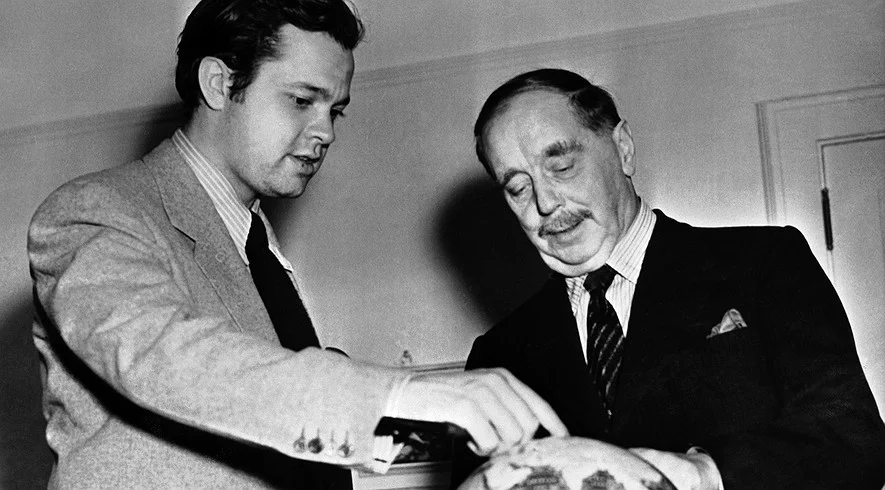

H.G. Wells with Orson Welles, 1940

On the subject of sitting down, Wells had some more to say.

“You must be comfortable, of course; an easy-chair with arm-rests, slippers, and a book to write upon are usually employed, and you must be fed recently, and your body clothed with ease rather than grandeur. For the rest, do not trouble to stick to your subject, or any subject; and take no thought for the editor or the reader, for your essay should be as spontaneous as the lilies of the field.”

Interestingly, for such a master of the art, essays are not about imparting information. “The value of an essay,” he writes, “is not its matter, but its mood.”

However, it wasn’t all this that I was thinking about at the end of another seemingly insurmountable week. I woke up remembering the very last paragraph of Wells’ essay—his advice on what to write at the start of one.

“An abrupt beginning is much admired,” he says, “after the fashion of the clown’s entry through the chemist’s window.”

I love this sentence and I think about it often. I get the ‘abrupt beginning,’ but what’s with the ‘clown’s entry through a chemist’s window’? The image of it makes me smile. It must be something quaint and peculiar to the late-1800s when the essay was written. Something like how Krusty the Clown in The Simpsons always bursts into a room with his signature, ‘Hey! Hey!’

But I know what Wells means with the clown thing. The best essays start like a popping balloon, right in the middle of some startling action, which you can’t help being swept up in.

It’s like how David Sedaris begins his New Yorker essay, “It’s Catching”:

“My friend Patsy was telling me a story. ‘So I’m at the movie theatre,’ she said, ‘and I’ve got my coat all neatly laid out against the back of my seat, when this guy comes along—’ And here I stopped her, because I’ve always wondered about this coat business. When I’m in a theatre, I either fold mine in my lap or throw it over my armrest, but Patsy tends to spread hers out, acting as if the seat back were cold, and she couldn’t possibly enjoy herself while it was suffering.”

Sedaris’s opening is nothing but a series of banalities, right? But they’re gripping banalities. There is action, characters, drama, tension—you want to read more.

But my very favourite opening is the very first sentence from George Orwell’s essay, “The Lion and the Unicorn”:

“As I write, highly civilised human beings are flying overhead, trying to kill me.”

Amazing. Written, of course, during World War II and the blitz bombing of London. The subtitle of Orwell’s essay is “Socialism and the English Genius”—you can imagine a drearier opening in lesser hands:

“Socialism has had a long and controversial history in England,” someone might write. “In recent years, many British people, blah, blah, blah...”

Snore.

But with Orwell, there’s no bland beginning. Instead, there’s the drone of engines, the whistling of bombs—not information but a palpable hum.

It’s ‘an abrupt beginning’ for sure, and just as shocking as a clown appearing out of f*cking nowhere while you’re waiting for a prescription.

Putting out fires with confetti

So that Friday morning, I was sitting in bed thinking about Wells’ essay and clowns and chemists’ windows, and I get a text message. The tutor who runs our Friday workshops is sick, so instead of a rare day off, I have to iron a shirt and stand in front of two classes being enthusiastic and engaging when all I want to do is stay home.

Later that day, after four straight hours teaching, it occurs to me that Wells’ advice about starting essays is also true of structuring classes. In fact, the whole last paragraph of his essay reflects what a good teacher does when they’re at their best:

“An abrupt beginning is much admired, after the fashion of the clown’s entry through the chemist’s window. Then whack at your reader at once, hit him over the head with the sausages, brisk him up with the poker, bundle him into the wheelbarrow, and so carry him away with you before he knows where you are. You can do what you like with a reader then, if you only keep him nicely on the move. So long as you are happy your reader will be so too.”

I think it’s the same when teaching. Actually, Wells was a teacher too—Winnie-the-Pooh author A.A. Milne was one of his students.

When starting a class, it’s best not to start with a dreary ‘Today we will be learning about the role of…”. Like Wells suggests, as with good essays, you have to hit them over the head with a story, a joke, an interesting fact or statistic—anything that makes them forget their phones for five minutes and pay attention.

Once you’ve got them, you have to carry them, the whole lot of them, like a rugby player or quarterback dragging the whole field along with you to the end goal, making sure no one’s lost, everyone’s paying attention, everyone’s engaged, and the whole lot are challenged enough so they’re extending themselves, but not too much that they tune-out or give up.

And now I realise the reason I remembered Wells’ quote that morning was nothing to do with essay writing; it was to remind me that it’s my job sometimes to be like a clown jumping through a chemist’s window. The class clown up-front each week doing a juggling act that’s not just about teaching course content, but also establishing a mood and an attitude towards learning, meaning-making and the world.

A teacher’s job is to keep everyone ticking along, steering some away from danger, telling others off with a wink and a joke when needed, putting out fires with confetti.

It’s a kind of light-hearted misdirection. All so you can keep them moving forward, without them realising it.

Thinking about it this way, I’m ok with being a clown.

Ant Gray

Painter Tracey Read talks about spending four weeks painting and drawing her way around Italy.