Pareidolia: Two Memories of Death

/A month or two ago, I bought this awesome book by Marion Denchars: Draw, Paint, Print Like the Great Artists. It has these simple exercises where you can muck around in the styles of Matisse, Warhol, Höch and others. In one exercise, you can make a Miró-inspired picture using an automatic drawing technique. What I got out of it was a wonky picture of a bird and two memories of death.

It goes something like this.

Take a large sheet of paper. Close your eyes. Using a big black marker, draw randomly all over the page in any combination of lines and curves and squiggles you like. Open your eyes. Now colour in or make something out of what you see.

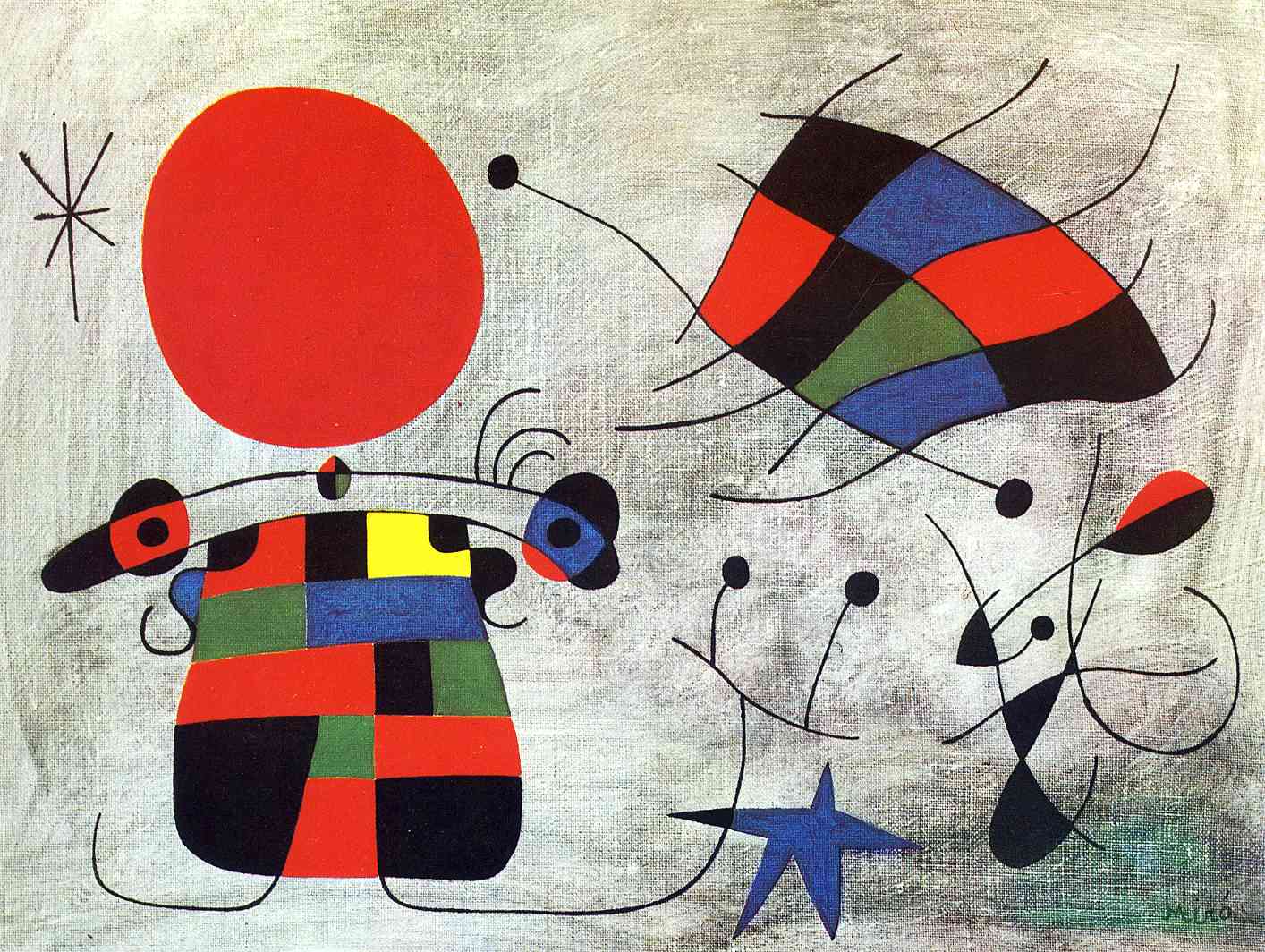

The Spanish/Catalan sculptor and painter Joan Miró used this technique to make pictures like this...

The Smile of the Flamboyant Wings, 1953

He learnt the technique of automatic drawing from André Masson...

Automatic Drawing, 1924

When I tried it, I instantly saw a bird in the shape I made. And while I added bits to it, this memory came up about a pet budgie called Bobbie that I had as a kid.

Bobbie was bright blue. He sat in the kitchen in his cage all day, singing and flicking seed all over the lino. I used to talk to him every morning when I got up. I was probably only three.

Slight detour: I didn't realise budgerigars were Australian birds. Not only that, but according to The New Encyclopedia of Birds they're the world's third most popular pet next to cats and dogs.

Anyway, one day, Bobbie wasn't in his cage. His disappearance confused me. Mum and dad told me he'd 'gone to up heaven,' but I was too young to understand what that meant.

When you're a kid, a lot of your concerns are practical. None of this arty-farty-abstract-euphemistic fluff—as kids we want facts. We need to know who, what, when, why. Logistics. Detail.

Did someone leave the cage open? Did Bobbie fly to heaven all by himself? Will he come back? If not, why not?

Later I heard them telling a neighbor they'd flushed him down the toilet, and the idea caused a schism in me: heaven was up; things in the toilet swirled around a few times and then got sucked downwards.

Why did they flush him? Did he do something wrong?! Were they going to do it to me if I did something wrong?!! Was the toilet how you got to heaven? Had I been pooping on paradise all this time?!!!

It's funny how the past can lie in wait for you in a random squiggle. I hadn't thought about Bobbie... well, in ever, and there he was staring back at me. Except it wasn't him; it was just my brain playing tricks on itself.

We make the world out of things we think we recognise. We're programmed to. It's called pareidolia.

Pareidolia is when we see familiar things in random splotches, lines and shapes. Pareidolia is the scientific explanation for why our brains jump on the suggestion of a black cat in tea leaves at the bottom of a mug, or the image of Jesus in the burn marks on our morning toast.

Pareidolia is another one of those evolutionary things. We're preprogrammed to see and find meaning in random shapes, like we sometimes do in clouds, because we come ready-made to seek out faces, to read expressions to distinguish friend from foe, to hunt for hints of camouflaged danger, and anything else that might hurt, help or hinder us.

When doves die

Second in line to the memory of Bobbie the Budgie that was triggered by my own little moment of 'pareidolic' recognition (if there is such a word) was another memory about a bird, and also about death.

I was older now. Maybe 13. There was a great and terrible-sounding commotion outside and I went to investigate. Before I consciously understood what was happening, I was already halfway across the lawn screaming at one of the cats. It ran off a little distance and stopped, looking back at me with a mixture of fear and disdain—a few white feathers hovering round its mouth. It had been attacking a dove which was now lying motionless.

I shouted at the cat again and it vanished over the garden fence. I went to look at the bird. It lay there, its head turned to one side and its opposite wing a little outstretched at an odd angle. It seemed uninjured, but I knew it wasn't. It looked like it was flattening itself out—becoming two-dimensional; like at any moment god's hand was going to reach down from the clouds, draw a chalk outline around it and pluck it away.

I stood there and looked at it helplessly. I watched as life retreated from its eyes. It was like when you turn an appliance off at the wall and the standby light fades out.

Just like that, it was gone.

A small unfocused blur, a standing chill

So while we're on the subject of death...

(I promise I won't leave you in this gloom. We're heading towards a bright turn at the end of this essay where we both stare at the moon. Not in a romantic way... Listen, stay with me. It'll be fun, I promise.)

I have a favourite poem about death. In fact, I think it's my favourite poem full stop. It's called "Aubade" by British poet Phillip Larkin. It's well worth a read in full, but for the purposes of brevity, I'll just give you the Cliff notes. (Or should I say 'jumping off a cliff notes'?)

(Sorry.)

In the poem, Larkin as narrator can't sleep. It's enormously early. He quickly realises what's not letting him sleep is the thing that will come to all of us as sure as the waking day: "What’s really always there," he says. "Unresting death, a whole day nearer now."

Yes, yes. Very gloomy. Very gothy.

Towards the end of the poem, Larkin writes:

And so it stays just on the edge of vision,

A small unfocused blur, a standing chill

That slows each impulse down to indecision.

Most things may never happen: this one will,

And realisation of it rages out

[...]

Death is no different whined at than withstood.

So what has this got to do with automatic drawing, my pet budgie, a dead dove and paraedolia? What links all these things are the lines: "And so it stays just on the edge of vision, / A small unfocused blur, a standing chill."

Death stands on the periphery like an understudy who knows everybody's part, and who will most definitely take the place of each and every one of us in the cast, one by one.

But until then, it waits. You can even find its trace in paradolia. Pareidolia helps us avoid death and danger, but is also equally looking for signs of life in everything too—finding it in clouds, on toast, in lots of weird and wonderful places—animate and inanimate, alive and dead.

In the last verse of Larkin's poem, dawn breaks and he sees death a little clearer:

Slowly light strengthens, and the room takes shape.

It stands plain as a wardrobe, what we know,

Have always known, know that we can’t escape,

Yet can’t accept. One side will have to go.

I never quite understood that line, "One side will have to go", but thinking back to the memory of the dove, I think I get it now. It's the difference between not understanding the death of my budgie, and then totally understanding what death means after seeing the life of the dove flicker and fade. "One side will have to go": when life leaves us, we have to leave our bodies behind. Part of us might go up to heaven if that's your thing, but the other part will be effectively fit to be flushed. But in all cases, the connection between body and spirit will be severed forever.

It's not an easy thing to contemplate. I guess that's why we spend so much of our lives trying not to think about it—trying to not be so glum about the inevitable. Like all those distractions and diversions Larkin lists at the end of his poem:

Meanwhile telephones crouch, getting ready to ring

In locked-up offices, and all the uncaring

Intricate rented world begins to rouse.

The sky is white as clay, with no sun.

Work has to be done.

Postmen like doctors go from house to house.

Except today it's not postmen; it's our Twitter or Facebook feeds.

A less gloomy ending (not for us, for the essay; we're all still gonna die)

Pareidolia literally translates as 'beside-image', which I think is apt—like a shadow; like that image that was waiting beneath the paper to receive the ink that made me remember I was trying to forget that my flickering light is only temporary.

'Aubade', the title of Larkin's poem? It means morning love song. It's the matching bookend to the word 'serenade.' A serenade is a song sung by lovers in the evening; an aubade is sung in the morning.

And the ending I promised with the moon? I didn't know this until recently, but speaking of pareidolia, there's a rabbit in the moon! Seriously. Some Chinese, Korean, Japanese and Mexican folk traditions have stories that relate to a rabbit-shaped pattern on the full moon's surface.

During Apollo 11's trip there in 1969, the following conversation was recorded:

Mission Control, Houston: Among the large headlines concerning Apollo this morning, is one asking that you watch for a lovely girl with a big rabbit. An ancient legend says a beautiful Chinese girl called Chang-O has been living there for 4,000 years. It seems she was banished to the Moon because she stole the pill of immortality from her husband. You might also look for her companion, a large Chinese rabbit, who is easy to spot since he is always standing on his hind feet in the shade of a cinnamon tree. The name of the rabbit is not reported.

Major General Michael Collins: Okay. We'll keep a close eye out for the bunny girl.

Rabbit

This week's Rabbit Hole is a double issue including a special guest post! Check out part one, "A Rabbit Hole of Denial".

Painter Tracey Read talks about spending four weeks painting and drawing her way around Italy.